I’m currently waiting for my family to rise for the morning, and reading Sergio Luzzatto, The First Fascist: The Sensational Life and Dark Legacy of the Marquis de Mores (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2026), and came across a contextual description of the historic landscape architecture in Cannes, southern France, where the Marquis (aka, Tony, or Antoine de Vallombrosa — names get really altered and complex when one is born into the invented tradition of the aristocracy) romped around as a child. Luzzatto does good in providing this 1870s-ish description of the social climate of this garden. I’ll just quote Luzzatto below here in this paragraph from page 30:

Already in the late 1860s, tourist guides were calling the garden of Villa Vallombrosa one of the major attractions of Cannes, praising the generosity of the owners for allowing tourists to visit “the magnificent garden.” It was an “authentic Eden,” insisted the accounts of the early 1870s. With the efforts of the skilled horticulturists the duchess hired to manage the garden, it was soon celebrated far beyond the limits of Provence. The crowds of visitors became so large that the duke decided to establish at the entrance a system for collecting donations to benefit the local hospice. As for the duchess, despite her health problems, her reputation as the driving force behind the elegant, salon-like, charitable society gathered on the Riviera ended up earning her — in the very guide that coined the name “Côte d’ Azur” — the posthumous title “Queen of Cannes.”

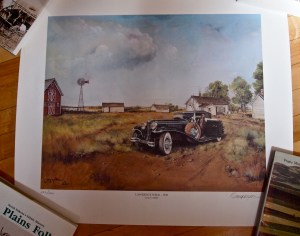

So this got me remembering an on the ground visit in the western North Dakota city of Medora the 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps heritage landscape architecture that is a garden dedicated to Tony, aka, Antoine de Vallombrosa, aka, the Marquis de Mores (one can extend their pinky finger while going through this name sequence if one wants). Have a look at the photos of mine below from a couple summers ago. Was the 1930s landscape architect who guided this CCC construction in Medora imagining a sort of symbolic nod to the 1860-70s fancy garden in Cannes, France that Tony spent his childhood running in? I don’t know. But all research begins with questions.

h of performances.

h of performances.