Every now and then, my own memory recalls when I was first assigned Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (Harper Collins, 1998, 1992). I would have been assigned it during an undergraduate class I took between 1999-2002 while at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, with the late professor Eric D. Weitz, and his squad of graduate teaching assistants. Attendance of the class was of the movie theatre scale. I got to thinking a bit more of Browning’s work (a solid 2025 letter is here, as he counters some specifics with another scholarly criticizer), especially in the context of what’s been playing out approximately 440 miles away (or 6.5 hours if you step on it), in Minneapolis, from where I’m at on the Northern Plains. I wanted to just simply blog a short on these thoughts. And note that it’s not okay for a population to send tax money to a system that uses that money to oppress its people. So there you go. Anyhow, my next morning meeting is on deck. So that’ll have to end this post.

Thinking About Patrick Byrne and America 250 and Little Bighorn/Greasy Grass 150

For some weeks now I’ve been imagining setting down some thoughts on some (how would one do ALL) historiography of the Irish Potato Famine from the 1840s and on. It has been research in prep for America 250 (1776-2026) this year, at least as it pertains to our region that is the Northern Plains. We (a growing group of us) are thinking about the Battle of Little Bighorn/Greasy Grass (LBH/GG) at 150 (1876-2026), as word arrived to Bismarck, northern Dakota Territory, on July 5, 1876 (about 11:00PM, as some local memorial markers indicate), that Custer and his command fell to the combined tribes of Oceti Sakowin and Northern Cheyenne. Yes: for you non-LBG/GG-o-philes, Custer’s command fell on the first centennial of the nation, at 100 years (1776-1876), so the memory of this is, and will, forever be interconnected with any and all national semiquincentennial, sestercentennial, bicesquicentennial, tercentennial, and it’ll just go on and on.

Stay with me here. So not too long after Custer and his command fell at LBH/GG, this Patrick Byrne chap arrives to the area, as an orphan immigrant from County Roscommon, Ireland, to Bismarck. He’s in his teenage years, yet. Byrne gets through local highschool, and at some point works with John Burke, another Irish-Northern Plainser who ended up being pretty successful navigating the political ladder in North Dakota and with U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. By that point, Byrne was a personal secretary to Burke (if you attain a certain threshold of monetary wealth, the paperwork can get so abundant that it’s a good idea to bring aboard a personal secretary — so I am told.). And Byrne puts his head down and works. But Byrne also works on his own historical memory project, Soldiers of the Plains, and intentionally has it published in 1926, which would have been the 50th observance (1876-1926) of LBH/GG. It may have been the first time, at least in 1926, that an immigrant settler researched, wrote about, and had published a narrative for an Anglo-American-reading audience that was empathetic and sympathetic toward the Oceti and Northern Cheyenne at LBG/GG.

The brick-by-brick historical case that I’m working up here goes something like this: when Byrne learned and read and heard the oral histories of LBH/GG, he understood exactly what was happening as he would have lived through it and exited Ireland because of it: the Anglo-sphere attempting to remove the local population so the Anglo-sphere could bring it into their own agricultural production, whether on the Northern Plains or in Ireland. Byrne would look at what happened on the Northern Plains, evaluated it with his own Irish life history, and said something to the effect of, “Same wine, different bottle.” So that’s what has brought me to Irish potato famine historiography: gotta see what has been researched and written about to be informed by it and also interconnect it with the larger research communities.

I looked through three titles which include Tim Pat Coogan, The Famine Plot: England’s Role in Ireland’s Greatest Tragedy (New York, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), John Kelly, The Graves are Walking: The Great Famine and the Saga of the Irish People (New York, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2012), and Padraic X. Scanlan, Rot: An Imperial History of the Irish Famine (New York City, New York: Basic Books, 2025). Because this happened around jultid, I also found myself revisiting Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol, originally published in 1843, just a couple years before the initial onset of the first wave of the Irish potato famine.

Now how did the potato famine happen? Scanlan and Kelly do a really thorough job of covering this in their works. It is a result of the Columbian Exchange. I’ll be as brief as possible here: in the 1530s, when the potato arrived to Portugal from Peru, it wasn’t the infinite variety of potato seeds that arrived to Portugal. Or lemme restart: potatoes brought from central and meso America to western Europe didn’t include every variety. It was just one or a couple. Then when western Europeans grew potatoes, they essentially used a singular variety and copies upon copies of that singular variety: so as the potatoes proliferated, it was kind of like a bad xerox of a bad xerox copy with each grown potato (you’d just lop off one eye of the potato, and plant it, you wouldn’t seed potatoes from a multitude of different origin seeds). So when the fungus of P. infestans proliferated, it completely decimated the copies of the copies of the same potato copy throughout Ireland, a bit in Scandinavia, and western Europe. The same fungus is pretty common in central and meso-America, but the potato varieties have over time developed immunity or resistance to that fungus. And the fungus needs certain weather and temperature conditions to really proliferate. These temp and weather conditions are literally perfect during growing season in Ireland.

The responses to this famine from London policy makers was abysmal. Scanlan does a good job of setting the sociological zeitgeist of the times that help inform readers why policy decisions were so abysmal: at first, in the 19th century, as in the latter part of the 18th century, political economists started growing tired of Imperial mercantilism, or a lot of “protectionist” and protectionist policies that would, well, protect the Imperial economy. Those who grew tired of it advocated for freedom, or this idea that if “natural” economic forces could just be allowed to play out, everything would be fine. We hear this narrative packaged yet today. Or things would at least be better. But that’s not what happened. And it so far has never happened. Maybe some day, right? There’s also a fallacy of “purity” at play in the minds of policy makers, or these certain types of policy makers: there is no such thing as pure, natural economy. It’s a fallacy to begin with. There are always influences, some strong, some ancillary, so to think a pure economy could exist would mean one believes an economy can somehow operate in a vacuum that is and is not connected with the human condition.

See how difficult it can be to try to get a tidy 15-page paper prepped for a singular America 250 conference? But back to Byrne. Byrne’s mother died in childbirth. And his father passed away when Byrne was really young. I’d have to revisit what from, but I think the cause was listed as influenza or pneumonia. But throughout Roscommon County, Ireland, the potato famine memories would be prolific. As would the narratives. Anyhow, jumping forward to 1926, Byrne had his Soldiers of the Plains published, and it’s an important text to recall, today, because it demonstrates the infinite messiness of the past. And also how the memory of Custer was, and has always been, just as messy when Custer was alive as when he wasn’t. Perhaps messier.

Thoughts on Condescension and Pretentiousness

I had a chance in the last couple days to visit an art center in a metropole in the Great Lakes region. While visiting, I got to thinking a bit about these spaces that are curated art spaces. And the resources that go towards, and have gone towards, their creation, maintenance and activation. And how this is a structural space for artists to show their art, thereby allowing the artist to have greater exposure, and even instilling in the artist a sense of making it. Within the art space (and this can be said for other art spaces) squads of staff help, instruct, or politely command visitors to behave in certain ways. This makes sense as the works of art cannot be (or often should not be) touched. Visitors also appreciate being instructed in the ways in which to behave in these spaces.

While at the art center, my mind also wandered toward thinking about the humanistic feelings of snobbery, condescension and pretentiousness, and how these feelings rise up out of human ether and into a kind of social structure. Like a group of people (potentially well financed) agreeing that one collection of art is worthy. And other bits of art are not worthy. The worthiness can in turn be a reflection of the actual material cultural product that is the art (whether fixed or ephemeral, or 2 dimensional art, such as on canvas or paper; or 3 dimensional art, such as mixed media or multi-material and so on). The worthiness can also be a reflection of perception. If an institution and the activators of the institution (such as a committee of individuals) decide, or are directed to decide by a director or museum conductor, that this or that person’s art is now needing to be worthified, then that work of art will be worthified. Then this worthification will be broadcast to art center membership, to past artists who have been worthified, to current artists being worthied, and to future artists who want worthification. It’s like a Gutenberg press to announce a cohesive media message that all readers are on board with. Or are told to be on board with. Like a ship requiring all hands on deck. So all this real feeling and structure then creates the idea that one is either in the artistic center, or they are not, or yet have to be. That is the creation of an other, or “an other.” It’s the feeling of there are us. And there are them.

Snobbery, pretentiousness, and condescension have an intellectual tradition. I cannot recall all titles. But some that come to mind are the following. The 19th century Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary, at least a piercing commentary on words and definitions from the time. Many seem to last. And there was Samuel Johnson, a person who manufactured and thought about snobbery, pretensions, and condescension from the London (not the Parisian) side of the channel circa 18th century. The Ancients have a real warehouse of this stuff. It’s the sort of stuff that inspired individual humans to develop philosophy. A sort of “wait a minute… what the eff did I just experience with that snob Alexander the Great? Why is he such a jerk? Let’s think about this for a bit…” Then boom, the rise of philosophical schools begins. Which creates even another “other,” as in the school of philosophy. It’s never ending. It’s just how it is.

So based on all these thoughts, I texted some friends. In some ways to insulate myself from potential feelings of inferiority within the metropole art center (it’s a punk rock sort of thing to do, or so I tell myself). But again, the substance of the texts had merit. How does one art. And when one arts, are we arting for the love of art? This is the central punk rock DNA we all have within ourselves. Or are we trying to art to become noticed by metropole art centers? It doesn’t have to be straight away one or the other, too. Like it could be percentage mixes. Without fixed percentages. Like percentages that were fluid throughout the day. I think the best texting arrived in a back and forth texting with a friend. We arrived at renaming the metropole art centers the following (it’s only proposed): The Center for Studies in the Acceleration of Pretentiousness and Condescension. It’s not meant to be a mean name. And not all artists or art consumers are pretentious. Or condescending. Very few are. Or very few want to create an other, where folks on one side of the fence attempt to project un-worthiness toward the other side of the fence. At the end of the day, condescension and pretentiousness only has power if a person allows it to have power. Like anything in life. Okay that’s all for this blog spot. Off to other things in the day.

More Landscape Memory of Driscoll, Burleigh County, North Dakota

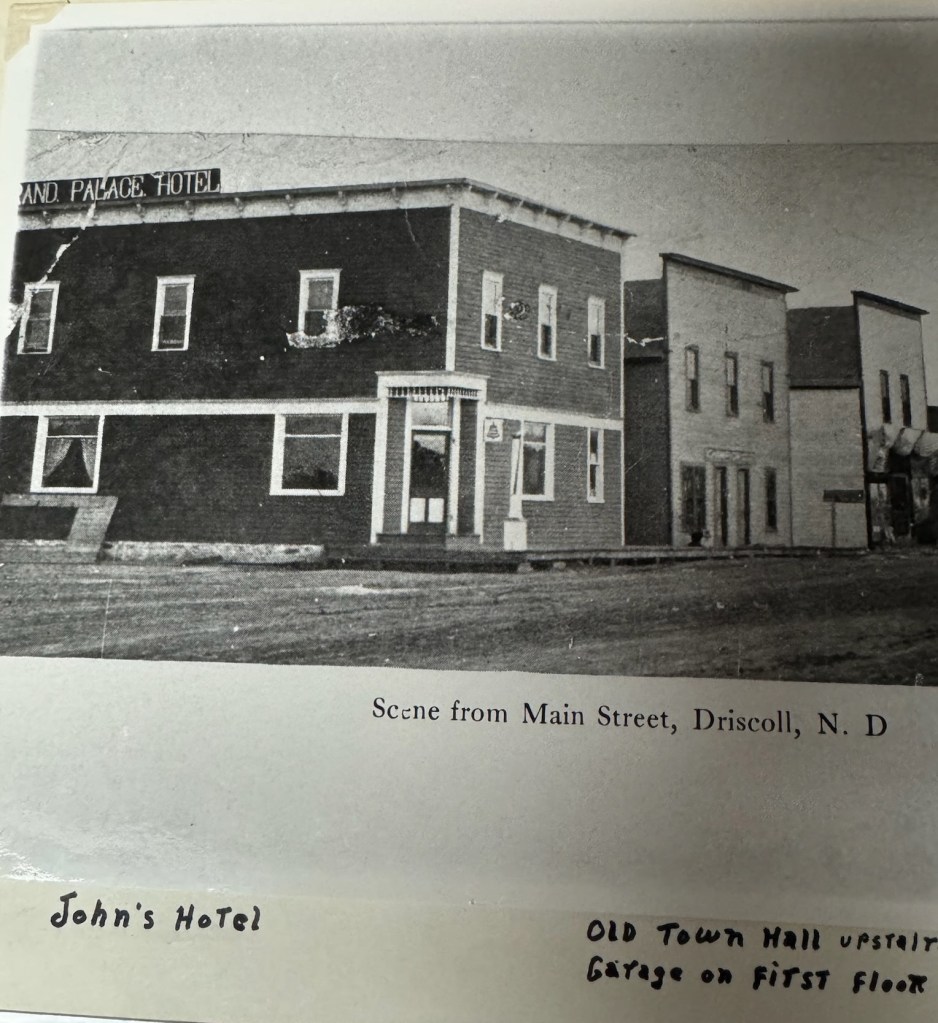

The last couple days I have been on a text message thread with a descendant of settlers who activated and ran Driscoll, Burleigh County, North Dakota, in the first couple decades of the twentieth century (let’s say from 1900 to 1920s or so). The text message thread came about as many months earlier I had been reading and blogging Era Bell Thompson’s memoir (some more here), one of two she wrote and published, American Daughter (University of Chicago Press, 1946).

In 1946, Era Bell, on page 21, provides a description of how she remembered Driscoll in the 1910s:

“Driscoll was a typical small North Dakota town, population about one hundred. Main Street, a broad, snow-packed road, was lined on both sides with frame store buildings, and its few homes were scattered out to the west of Main and south toward the Lutheran and Protestant cemeteries. A four-room consolidated school sat upon a hill, midway between the cemeteries and town.”

On August 3, 2025, I had a chance to stop along where the north-south automotive road crossed the east-west railroad tracks at Driscoll in an attempts to better acquaint myself with the landscape, and imagine what had been 110 years prior. Fast forward to this week of December 14, 2025, and the text message thread: Kate Herzog (also a commissioner for Bismarck Parks & Recreation District) mentioned some of her great grandparents owned the Grand Palace Hotel, she thinks in the 1910s. Perhaps a bit later. Now cut back to Era Bell Thompson’s 1946 memory of her family relocating from a house “to the empty hotel on the edge of town” (page 26 of American Daughter). Was this the same hotel? I mean, how many hotels could have a town of approximately 100 people supported in the 1910s?

Of the hotel, Era Bell said,

“The hotel was an old, eighteen-room barn of a building, bare and cold, but we set up living quarters in the spacious kitchen, and that night Pop made southern hoecake on top of hte gigantic range and fried thick steaks in butter. The tightness was gone from the corners of his eyes as he threw his head back and sang, ‘I’m so glad, trouble don’t last alway, Oh, I’m so glad, trouble don’t last alway.'”

Also within Era Bell Thompson’s memoir is a Norwegian store owner and clerk identified as “Old Lady Anderson.” Herzog mentioned she had Norwegian kin in Driscoll with the surname Hanson. Are these interconnected somehow? Era Bell also mentioned an Oscar Olson, and a Hank Hansmeyer, the local blacksmith who offered the Thompson family land to share crop on a quarter section that had yet to be picked clear of glacial rock deposits. Era Bell recounted the agreement (page 29): “Hank… would furnish the land, the buildings, and the horses if we… would furnish the seed, do the work, and give him half the profits.”

There’s nothing definitive from this blog entry of mine. Only a continued fascination of the layers of meaning on a particular landscape. A landscape that could otherwise feel “like nothing is HERE!!!” We’ve heard this all too many times from visitors of our rural, or “rural.” Without this meaning, without the intentional and sustained want of us in the present to incrementally scratch the layers away to find out what has happened here in the written, published, and oral historical record, it may well remain a superficial place of “nothingness.” But there’s a lot going on here. A lot today. A lot from yesterday. It’s a model used by the fancier Simon Schama in his Landscape and Memory (Vintage, 1996). I’ll keep chugging on this. But for now, at least I’ve been able to locate in the present the person (Kate Herzog) who will help lead any real or imagined future landscape memory bus tours to Driscoll in eastern Burleigh County, North Dakota.

Reading Joseph M. Marshall III’s Hundred in the Hand

Some weeks or months ago, while in conversation, Dakota Goodhouse mentioned the name of the late Joseph M. Marshall III. I scribbled it down and got to searching on the webs. Turns out he went to the other side in April 2025, but before that he set down a magnificent body of history, cultural history, and novels in the original sense of the word: new ideas.

Last night, and in between first and second sleeps, I continued cruising through Marshall’s Hundred in the Hand (Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing, 2007), described on the coverpage, appropriately, as Lakota Westerns (it’s good to read the plural, as it suggests there is, or will be, more than one).

Reading Marshall III got me thinking about analogies: finding out about Marshall III was similar to finding out about the late Peter La Farge’s work of folk songs, and how Johnny Cash took up numerous songs of La Farge and popularized them. The analogy my brain was running is like this: it seems I’m only now finding out about this amazing historian, artist, folk singer, novelist. It is good stuff.

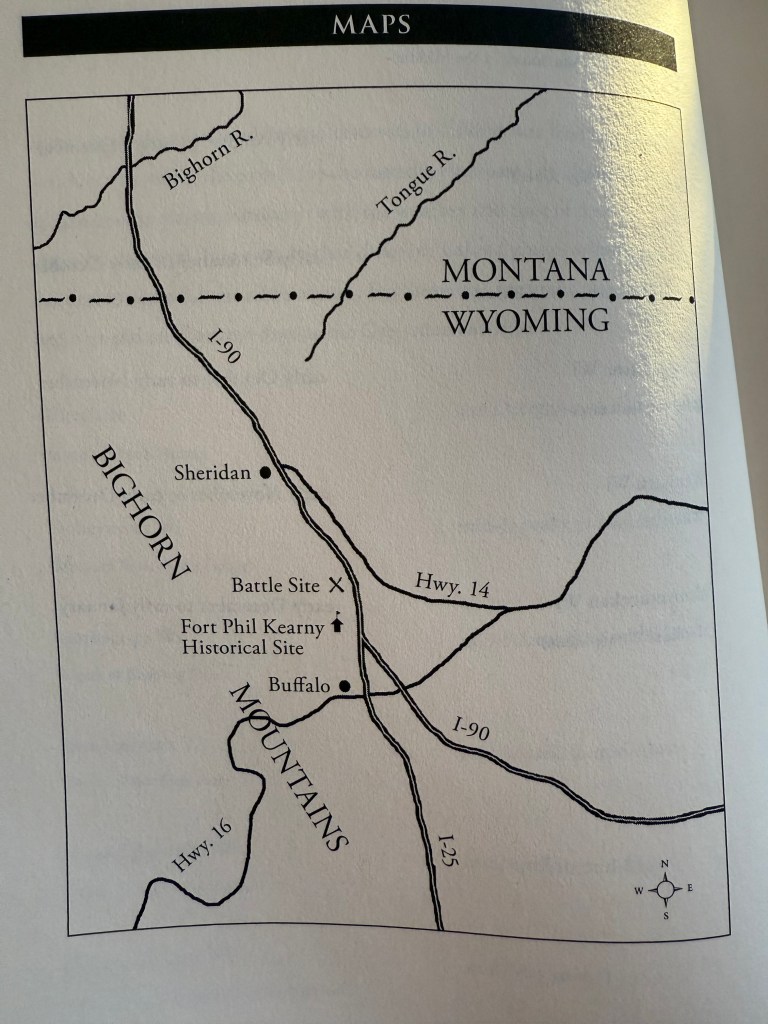

As to Marshall III’s Hundred in the Hand: this morning I texted Goodhouse, “It paints Lakota culture across the 1860s northern plains landscape. Daily lives. It’s good.” The novel takes a reader into a post-American Civil War landscape where the Great Plains mingles with the eastern elevation of Rocky Mountains in today’s Dakotas, Wyoming, Montana, and Nebraska with the characters involved with the specifics of the Bozeman Trail, or what Marshall III notes was called the Powder River Road or, as described in the introductory Lakota to Euro-American glossary, Makablu Wakpa Canku. Marshall III also dictionaries (now a verb) several other landscape names: He Wiyakpa or He Ska (Shining Mountains or White Mountains) = Bighorn Mountains; Canku Wakan Ske Kin (The Road Said to be Holy or Holy Road) = Oregon Trail; Hehaka Wakpa (Elk River) = Yellowstone River; and several others.

The geological river and creek valleys and buttes filled in with the small islands of cottonwoods, amidst a sea of scrub grasses, sage, and cacti. Layered into and upon this is the day to day lives of Lakota, circa 1866, who are understandably frustrated with watching increasing waves of Euro-American gold-seekers migrate through and post up in their country. Without going too much further into it all (save that for reading it yourself), I’d recommend reading Marshall III’s Hundred in the Hand. It adds a greater layer of texture to the region it describes. Needed layers. Historical works often narrate the historical events informed by historical documents (those primary sources) that are created by and for historic bureaucracies: the structures of nation states. Marshall III’s novel allows a reader into the cultural window of a regional northern plains landscape. The smells. The feel of summer heat. The cool of summer night. The tastes of elk stew in the surround of a hide tipi.

The takeaways from this novel thus far? I’ll work in groups of three. The first is that 1866, and Red Cloud’s defense of his people’s country that culminated in the Fetterman Fight, was one of several prologues to the Battle of Greasy Grass/Little Bighorn a decade later. Lakota who fought in 1866 would remember this as one of many as the spring of 1876 approached. Why is this important? As we approach America 250, it will forever coincide with the centennial observance of the June 25, 1876 Battle of Greasy Grass/Little Bighorn, and the various conversations had in the Anglo-American Sphere when news hit the newspapers just after the Bismarck Tribune wired narratives to the New York Herald on July 5, 1876, and the subsequent days after. A second reason take away is the perceptive shift the novel takes the reader on: it reminded me a bit of what Patrick Byrne would like, or would have liked to read, the author of Soldiers of the Plains, a 1926 publication that brought a native perspective to an Anglo-American readership fifty years after the Battle of Little Bighorn. Byrne, who emigrated from Ireland as an orphan, and eventually arrived to Bismarck, Dakota Territory, would understand what Anglosphere Colonization looked like, having seen and heard the recent memories of the potato famines in Ireland, and the Anglosphere’s complete inability to respond in a humanitarian way.

Where are we at with the 3rd takeaway? Regionalism. Unique things have happened, and continue to happen, in the various regions of the world. It’s not that one region is better than another. It’s that things happen in regions. People live out lives in these regions. They are worth considering and thinking about. This, as it goes, leads to an appreciation of regions, and it gives those regions infinite cultural depth in the face of standardized horizontal and vertical strip mall culture (which has its own value of standardized consistency, don’t get me wrong).

Reading About These American States, 1920s and 1990s

We have just passed the autumn equinox of 2025, and are just 3 months away from 2026, which has been identified nationally as the quarter millennium of America’s origins — this ongoing experiment in republican democracy. As historians go down research rabbit holes (one thing just constantly leads to another), the rabbit hole I’ve tunneled has arrived, this week, to a couple different collections of essays. Starting from the present, the first collection is John Leonard’s edited volume of These United States: Original Essays by Leading American Writers on Their State Within the Union (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2003) and, what I’ve been enjoying all the more, is what editor Daniel H. Borus scooped together with the collection of These United States: Portraits of America from the 1920s (Ithaca, New. York: Cornell University Press, 1992).

The essays are just that, what is within the subtitle of the two works: a writer was found or identified of each state in the Union. And they were asked and/or commissioned to produce a work on their state of the state. In the 1920s, 49 essays were collected (no Alaska and Hawaii yet in the nation, but they provided the State of New York with two essayists). I found this larger collection of essays through the earlier location of Willa Cather’s 1923 essay “Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle” (which resonates today). Rolling north to south on the Great Plains, and then the north to south western states, the 10 writers and essays go like this:

- Robert George Paterson “North Dakota: A Twentieth-Century Valley Forge”

- Hayden Carruth “South Dakota: State without End”

- Willa Sibert Cather, “Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle”

- William Allen White, “Kansas: A Puritan Survival”

- Burton Rascoe, “Oklahoma: Low Jacks and the Crooked Game”

- George Clifton Edwards, “Texas: The Big Southwestern Specimen”

- Arthur Fisher, “Montana: Land of the Copper Collar”

- Walter C. Hawes, “Wyoming: A Maverick Citizenry”

- Easley S. Jones, “Colorado: Two Generations”

- Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, “New Mexico: A Relic of Ancient America”

Rather than trying to punch out any more blog analytics here, I’m going to take the rest of this morning to pick up at the 4th listed essay above, as I’ve been digesting them in the order listed above. More to report on a bit later.

Clell Gannon “SoBGA” Re-Release

I thought I’d prep some mental notes, or quotes, in this blog post as it regards what I’ll send up to Bill Caraher at The Digital Press at University of North Dakota. Caraher prompted me to think of some quotes to include in the release, or re-release (1924 to 2025), of Clell Gannon, Songs of the Bunch Grass Acres and “A Short Account of a Rowboat Journey from Medora to Bismarck” (Grand Forks: The Digital Press at U of North Dakota, 2025). Below are potential quotes.

- “If you love the Northern Plains, and are in any of these arts, crafts, or trades, you will want to make time to read Clell Gannon, as his life and poetry intersected with them all: farmer, star gazer, kayaker, rancher (cowgirl and cowboy), canoe-er, lawyer, cow-boy or -girl poet, architect, Boy Scout troop leader, tourism coordinator/planner/guide, landscape architect, administrator (private or public), underwriter (banking or insurance), artist (digital or graphic, folk, traditional commercial, print-maker, muralist), elected policy maker (county), Great Plains-ist, historical interpreter, judge (appointed or elected), architectural historian, conservationist (hunting and fishing), park supervisor (city, county, state, federal), Theodore Roosevelt-iophile, historian, horticulturalist, archaeologist, or anthropologist. This list is not exhaustive.”

- The above narrative touches on a lot of correct points. But it’s way too long. Brevity is needed. Perhaps with a question prompt to the reader.

- “Ever float a kayak or canoe from Medora to Bismarck, down the Little Missouri River and Missouri River? Clell Gannon, George Will, and Russell Reid did. In the 1920s. And Gannon explained a lot of historical and cultural sites along the way.”

- The above is better for brevity. It hits a certain demographic, too. Not everyone imagines or physically floats down inland continental waterways. I mean everyone should. But they don’t.

- “Clell Gannon is a window into how we all shape the landscape we live in, and how that same landscape shapes us. Gannon explains this in philosophy, manifesto and his art of life by and for the Northern Plains.”

- This is getting closer. Below I try to craft another one using the lexicon from modern politics.

- “Anyone who doesn’t read this book is a loser, plain and simple. Not a winner. A total loser. And why would anyone want to be a loser? There’s no reason. Buy this book from The Digital Press. It’s so wonderful. Probably one of the best if not thee best book out there on the Northern Plains. Easily. No contest.”

- I won’t go with the above. But it was joyously absurd to craft. It’s important to wrap one’s arms around absurdity. Own it. Otherwise it’ll own you.

Era Bell Thompson Local and Global: Windshield Reconnoiter in Driscoll, Burleigh County, North Dakota

A week or so ago (August 3, 2025), I pulled off a section of Interstate 94 in North Dakota, I-94 Exit 190, in eastern Burleigh County. I’ve been reading the two published works by Era Bell Thompson, American Daughter (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946), and Africa: Land of My Fathers (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc.: 1954).

Published in Post-WWII America, in a span of 8 years, these works take the reader from the Iowa to the Northern Plains to Chicago, and across the Atlantic Ocean to Thompson’s attempts at ancestral genesis locus. While reading the latter, last night Thompson was navigating 1950 (or thereabouts) Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and layers upon layers of colonization that arrived to the present.

At page 201, Thompson republished verbatim the slip of paper that prevented her from being able to freely see this section of East Africa:

“NOTICE TO PROHIBITED IMMIGRANT

…Take notice that I have decided that you are a prohibited immigrant on the grounds that your entry in Zanzibar is undesirable. You are hereby ordered to remain on board and to leave Zanzibar by the aircraft in which you arrived at Zanzibar.”

Thompson says it was signed by an agent of the Principal Immigration Officer of Zanzibar. Reading this felt like similar wine, but different bottle. History resonates that way.

It also got me thinking about how, as the time barge continues pulling us into new iterations of the present, how historians might think of ways to communicate the past to present and future generations. And provide theoretical models in which to understand those infinite pasts. How does one, for example, teach the long nineteenth century to, say, a 4th or 8th grader? It can, at that last sentence, initially feel just completely overwhelming. I mean, so much happened: empires (British, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Netherlands) duking it out. Locals and globals on the ground, perhaps carrying the flag of their dwindling empire, or hoisting a new flag of this or that nation or nation state. And all this, trying to navigate the rubric of global capitalism, locals with traditional barter trade systems that remained relevant for generations upon generations, these same barter systems now swimming in similar waters as industrial global capitalism.

But getting back to it: this is where sense of place really matters. A person should pick up Era Bell Thompson’s books. Read them. And then consider relocating themselves, in the present, as approximately close as they can safely and legally get to her global and local footprints. I’ll keep on that course.

Northern Plains, Urbs in Horto, Era Bell Thompson

Three days ago it was my intent to blog some analog (lots of hand writing) notes I’ve been taking while digesting Era Bell Thompson’s 1946 memoir, American Daughter (University of Chicago Press). In 2025, doing anything analog is radical, aka, returning to the roots. So I picked it back up this late afternoon, June 22, 2025. The June 20, 2025 Summer Solstice derecho that ripped across central and eastern Northern Plains dropped 13 documented tornados (this one just east of Jamestown, near Spiritwood, video here) had everyone occupied with setting up temporary sleeping quarters in basements, and, later, trimming downed trees, along with checking in with loved ones from beginning to end from Bismarck to Jamestown to Valley City to Fargo to Grand Forks. Tragically and sadly the derecho’s violence took three to the other side.

Back to Era Bell Thompson. Two themes (non -exhaustive or -definitive) emerge from American Daughter:

Thompson narrates Northern Plains landscape beauty which, unless you as a reader don’t know this already, is part of the Great Plains literary canon. I imagine her narrative could apply to all grasslands ecosystems throughout the planet. But, specifically of eastern Burleigh County, North Dakota, in the vicinity of Driscoll, circa 1910s, have a look at this passage:

“It was a strange and beautiful country my father had come to, so big and boundless he could look for miles and miles out over the golden prairies and follow the unbroken horizon where the midday blue met the bare peaks of the distant hills.

No tree or bush to break the view, miles and miles of prairie hay-lands, acre after acre of waving grain, and, up above, God and that fiery chariot which beat remorsely down upon the parching earth.

The evenings, bringing relief, brought also a greater, lonelier beauty. A crimson blur in the west marked the waning of the sun, the purple haze of the hills crept down to pursue the retreating glow, and the whole new world was hushed in peace.

Now and then the silence was broken by the clear notes of a meadow lark on a near-by fence or the weird honk of wild geese far, far above, winging their solitary way south.

This was God’s country. There was something in the vast stillness that spoke to the man’s soul, and he loved it.

But not the first day.”

Which leads to a second non-chronological theme: while on the farm in Driscoll, everyone but a few seemed to be in debt. The land was rented. Dwellings were rented. Money was borrowed to purchase equipment. Yet, while banker notes lingered over the heads of everyone, all farmers were still free. In her narrative leading up to page 49, Thompson lays the foundation for the lead up to farming working class revolution that swept the 1910s Northern Plains. Thompson speaks to her father’s perception of the 1916 rise of the Nonpartisan League on pages 50-51, teasing out the tension between the urban and rural:

“In 1915 a growing rebellion against ‘big business’ and the ‘city fellers’ resulted in the formation of the Nonpartisan League, a political organization composed entirely of farmers. The League swept the country like a prairie fire… My father was cheered by this odd turn of events. When he left politics back in Des Moines, [Iowa] a rock-bound farm in the middle of North Dakota was the last place in the world he expected to find it again; but there it was, all about him, on the tongues of everyone, for the farmers were up in arms, drunk with their sudden strength and powers… That Saturday Pop went to Steele with Gus and Oscar Olson and August Nordland for a political rally at the Farmer’s Union hall. Something about Townley, the dynamic little organizer, inspired Pop, set him to thinking. Two weeks later, when Lynn J. Frazier, the League’s gubernatorial candidate, came through Driscoll campaigning, Pop was the first to shake his hand.”

I’ll continue to analog my way through American Daughter. On chapter 4, now. I got to texting a bit about Era Bell Thompson with Bernard Turner with Bronzeville-Black Metropolis National Heritage Area (BBMNHA). It turns out Thompson’s papers are with the Chicago Public Library, linked here. Bernard and I are optimistic about developing a BBMNHA and Northern Plains NHA talk. Thompson was a part of both the urban and rural in Great Plains and Midwest history, and all the comparisons and contrasts and tensions that entailed. My next scheduled stop will be to get on the ground in and around Driscoll, to revisit the Era Bell Thompson sense of place. Be like Herodotus: also plan visits to go where the history was made, urban or rural. More to come on that.