Just pecking out some more notes to add to the texture of the Clell Gannon project, working on revisions with The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota (Grand Forks).

After revisiting Willa Cather’s 1923 (September 5) essay, “NEBRASKA: The End of the First Cycle” in The Nation (117: 236-238), and particularly after reading Cather’s demographic cross section slice of a day in the life of 1923 Nebraska: “On Sunday we could drive to a Norwegian church and listen to a sermon in that language, or a Danish or a Swedish church. We could go to the French Catholic settlement in the next county and hear a sermon in French, or into the Bohemian townschip and hear one in Czech, or we could go to church with the German Lutherans. There were, of course, American [meaning American English] congregations also… I have walked about the streets of Wilber, the county seat of Saline County, for a whole day without hearing a word of English spoken.” And, a couple sentences later, Cather notes that “Our lawmakers have a rooted conviction that a boy can be a better American if he speaks only one language than if he speaks two.”

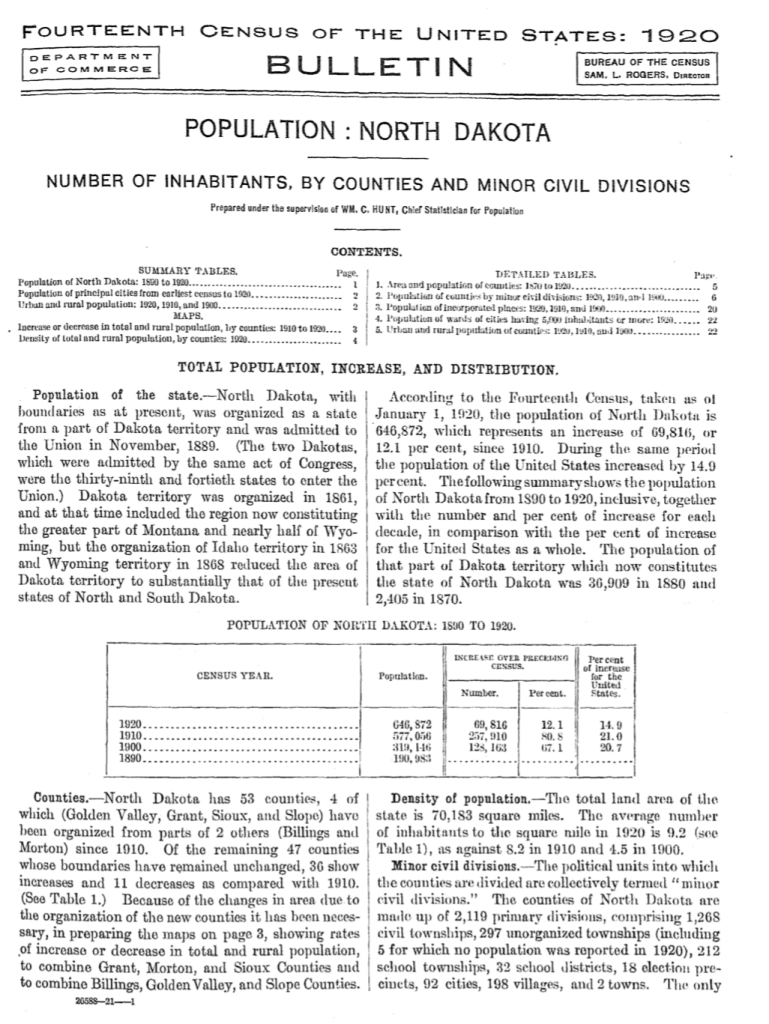

North Dakota, in the year 1900, also had a diverse immigrant population with a greater percentage of foreign-born than any other state at that time in the Union. I don’t have the percentage number right in front of me. But from memory it is something like 78% foreign born. Prairie Mosaic is the reference I’ll double check to confirm that number, as this provides ethnohistoric ground-truthing, research that took place from the 1960s through the decades following said 1960s.

This returns to Clell, and thinking about the context in which he wrote his Songs of the Bunch Grass Acres, and the reading audience who had want or access to his 1924 Western Americana poems. In 1920, Orin G. Libby’s article, “The Arikara Narrative of the Campaign Against the Hostile Dakotas — June, 1876” ran in North Dakota Historical Collections (Bismarck, North Dakota, Volume 6). Aaron McGaffey Beede collaborated with Libby on this. Beede was the interpretive and translation conduit between the Arikara scouts and Libby. Libby’s approach was one that would speak to Custer-philes, with an angle that may appeal to Custer-philes who may have had a broad brush stroke (see racist) outlook on all of Native America. With Libby popularizing how Arikara fought alongside the U.S. Military in 1876, he was making a pitch (fortified with numerous data points) that demonstrated their patriotism. In 1918, two years before Libby published his Arikara narratives, the Great War ceasefire (armistice) happened. Up to 12,000 Native American soldiers participated in World War I, this at a time when Native Americans still didn’t have the right to vote. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 would change all of this, allowing tribal citizens the Federal status of voting. However, the U.S. Constitution still left it up to individual states to decide who had the right to vote. So Libby’s narrative that set down the Arikara memories of the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn/Greasy Grass would also have spoken to that political activist line of thinking.

So what does all this mean of and for Clell Gannon’s 1924 Songs of the Bunch Grass Acres? I don’t have much more to say beyond the above, other than this is some of the context in which Clell wrote. A multitude of ethnic languages from the immigrant populations could be encountered in the urban and rural of the Great Plains and American West. Tribal citizens were granted another incremental federal right to vote. Libby lobbied on the Arikara behalf through historical memory and narrative. And Clell continued his relationship with the major shapers of the early State Historical Society of North Dakota, making his poetic contribution to the love of northern plains place through said poems.