Some weeks or months ago, while in conversation, Dakota Goodhouse mentioned the name of the late Joseph M. Marshall III. I scribbled it down and got to searching on the webs. Turns out he went to the other side in April 2025, but before that he set down a magnificent body of history, cultural history, and novels in the original sense of the word: new ideas.

Last night, and in between first and second sleeps, I continued cruising through Marshall’s Hundred in the Hand (Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing, 2007), described on the coverpage, appropriately, as Lakota Westerns (it’s good to read the plural, as it suggests there is, or will be, more than one).

Reading Marshall III got me thinking about analogies: finding out about Marshall III was similar to finding out about the late Peter La Farge’s work of folk songs, and how Johnny Cash took up numerous songs of La Farge and popularized them. The analogy my brain was running is like this: it seems I’m only now finding out about this amazing historian, artist, folk singer, novelist. It is good stuff.

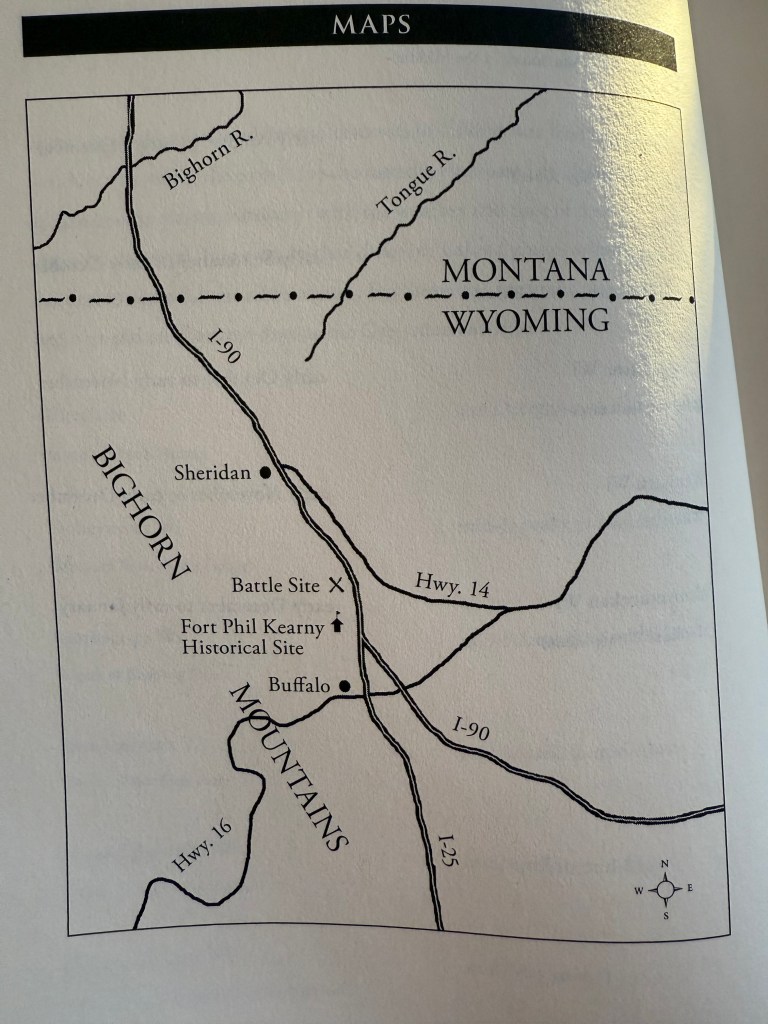

As to Marshall III’s Hundred in the Hand: this morning I texted Goodhouse, “It paints Lakota culture across the 1860s northern plains landscape. Daily lives. It’s good.” The novel takes a reader into a post-American Civil War landscape where the Great Plains mingles with the eastern elevation of Rocky Mountains in today’s Dakotas, Wyoming, Montana, and Nebraska with the characters involved with the specifics of the Bozeman Trail, or what Marshall III notes was called the Powder River Road or, as described in the introductory Lakota to Euro-American glossary, Makablu Wakpa Canku. Marshall III also dictionaries (now a verb) several other landscape names: He Wiyakpa or He Ska (Shining Mountains or White Mountains) = Bighorn Mountains; Canku Wakan Ske Kin (The Road Said to be Holy or Holy Road) = Oregon Trail; Hehaka Wakpa (Elk River) = Yellowstone River; and several others.

The geological river and creek valleys and buttes filled in with the small islands of cottonwoods, amidst a sea of scrub grasses, sage, and cacti. Layered into and upon this is the day to day lives of Lakota, circa 1866, who are understandably frustrated with watching increasing waves of Euro-American gold-seekers migrate through and post up in their country. Without going too much further into it all (save that for reading it yourself), I’d recommend reading Marshall III’s Hundred in the Hand. It adds a greater layer of texture to the region it describes. Needed layers. Historical works often narrate the historical events informed by historical documents (those primary sources) that are created by and for historic bureaucracies: the structures of nation states. Marshall III’s novel allows a reader into the cultural window of a regional northern plains landscape. The smells. The feel of summer heat. The cool of summer night. The tastes of elk stew in the surround of a hide tipi.

The takeaways from this novel thus far? I’ll work in groups of three. The first is that 1866, and Red Cloud’s defense of his people’s country that culminated in the Fetterman Fight, was one of several prologues to the Battle of Greasy Grass/Little Bighorn a decade later. Lakota who fought in 1866 would remember this as one of many as the spring of 1876 approached. Why is this important? As we approach America 250, it will forever coincide with the centennial observance of the June 25, 1876 Battle of Greasy Grass/Little Bighorn, and the various conversations had in the Anglo-American Sphere when news hit the newspapers just after the Bismarck Tribune wired narratives to the New York Herald on July 5, 1876, and the subsequent days after. A second reason take away is the perceptive shift the novel takes the reader on: it reminded me a bit of what Patrick Byrne would like, or would have liked to read, the author of Soldiers of the Plains, a 1926 publication that brought a native perspective to an Anglo-American readership fifty years after the Battle of Little Bighorn. Byrne, who emigrated from Ireland as an orphan, and eventually arrived to Bismarck, Dakota Territory, would understand what Anglosphere Colonization looked like, having seen and heard the recent memories of the potato famines in Ireland, and the Anglosphere’s complete inability to respond in a humanitarian way.

Where are we at with the 3rd takeaway? Regionalism. Unique things have happened, and continue to happen, in the various regions of the world. It’s not that one region is better than another. It’s that things happen in regions. People live out lives in these regions. They are worth considering and thinking about. This, as it goes, leads to an appreciation of regions, and it gives those regions infinite cultural depth in the face of standardized horizontal and vertical strip mall culture (which has its own value of standardized consistency, don’t get me wrong).