Reinhard and Rothaus set out on the first day of Adventure Science’s fieldwork in western North Dakota.

This morning I’ve been listening to one of Adventure Science‘s raw audio press conferences and forums, this concerning the latest trek through the badlands of western North Dakota, and I couldn’t stop thinking about the divide between the hard and soft sciences and the humanities, and how it is so necessary for conversations to take place between them (another interview from Prairie Public can be found here). Throughout academia, this is often called “crossing disciplinary lines.” In non-academic jargon, this means that you walk down the hall or out the building and across the courtyard to someone else’s office, kitchen, machine shop or garage, and ask her or him why and how they are working on a problem, whether an abstract theorem or a carburetor.

In the case of this Adventure Science press conference (which everyone should listen to at least once), Simon Donato and Richard Rothaus explain at the outset that they undertook this project in a completely scientific and objective fashion, and by this they were not obligated to produce — ahem — results for one public or private group or another. This is true, to a point. Yet the cultures that we are born into also contributes to the way we see the world, and consciously or unconsciously we will speak to a variety of these groups whether we like it or not.

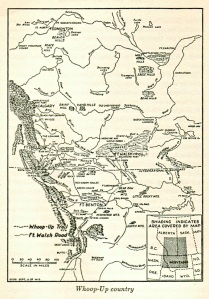

I was thinking about this in relation to an observation Simon, who hails from the culture of Alberta, Canada (this is important, just stay with me here), made about half way into the press conference or conversation (or press conference-sation). In the history of the British-Canadian West and the American West, Euro-American settlement above and below the 49th parallel played out in much different ways. Simon consciously or unconsciously hints at this. There is historical reason for this (something the late historian Paul Sharp researched at-length, and some comments on that here and here).

In the history of the Canadian West, Anglo- and Euro-American settlement was deliberate. This is often symbolized by the Royal Canadian Mounties, who would patrol and police the areas, ensuring that the Crown’s Law and Order would be maintained across all the land, and ideally across the global empire. Through this order, land would be settled in an orderly fashion, and be made “useful” and useful for the commonwealth and crown (see Thomas Hobbes for intellectual exegesis). If coming from that Canadian backdrop, either yesteryear and today, when you enter the American West, including western North Dakota, it still looks like a crazed free-for-all, even in the wilderness. At the Adventure Science forum, beginning at 35:20 in the audio, Simon said,

…As we got into some of the ranching areas where, again it’s vast, you know you feel like you’re kind of on the edge of a wilderness area, but there’s no houses… there’s fences, there’s obviously been cattle through there, but there’s no houses and no structures at all, and that was really surprising to me. Where I’m from in Alberta, if you got fences, there’s gonna be a farmhouse somewhere, there’s gonna be a barn somewhere. You get into these areas, and I was really surprised that I didn’t find these structures out there, I mean, not even hunting cabins.

So I guess what Simon hints at and what I’m communicating here is that yes, science tries to be as objective as possible. But there is no amount of finality to that objective science, because as cultures evolve, so does science, and so do perceptions. What appears normal to one person will be abnormal to an outsider. This is why cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary studies and conversations absolutely have to take place, and this is why it is worth our while to conserve and preserve some of these places (one of the reasons Theodore Roosevelt set up the national parks).

Note: Native America/First Nations had occupied these badlands and North America for millenia, at least 12,000 to 13,000 years (and even this is contested by Native friends, as they have told me much longer), before non-Natives got to the area. Even the fact that we call a wilderness a “wilderness” today is a cultural bias worthy of consideration and contemplation.